- Home

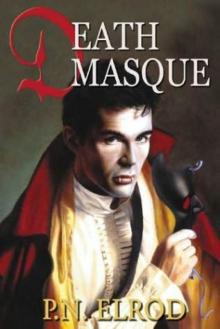

- Death Masque(Lit)

P N Elrod - Barrett 3 - Death Masque Page 3

P N Elrod - Barrett 3 - Death Masque Read online

Page 3

"Why not? You once said that Miss Jones found it to be exceedingly pleasurable."

"True, but we've also surmised that it led to this change manifesting itself in me."

"But it was a good thing-"

"I'll not deny it, but until I know all there is to know about my condition, I have not the right to inflict it upon another."

"But Miss Jones did so without consulting you."

"Yes, and that is one of the many questions that lie between us. Anyway, just because she did it, doesn't mean that I have to; it smacks of irresponsibility, don't you know."

"I hope you don't hate her." She said it in almost exactly the same tone that Molly Audy had used, giving me quite a sharp turn. "Something wrong?"

"Perhaps there is. That's the second time anyone's voiced that sentiment to me. Makes me wonder about myself."

"You do seem very grim when you speak of her."

"Well, we both know all about betrayal, don't we?"

Elizabeth's mouth thinned. "The nature of mine was rather different from yours."

"But the feelings engendered are the same. Nora hurt me very much by sending me away, by making me forget, by not telling me the consequence of our exchanges. That's what this whole miserable voyage is about, so 1 can find her and ask her why."

"I know. I can only pray that whatever answers you get can give you some peace in your heart. At least I know why I was betrayed."

We were silent for a time. The candles had burned down quite a bit. I rose and went 'round to them, blowing out all but two, which I brought over to place on a side table near us.

"Is that enough light for you?" I asked.

"It's fine." She gave herself a little shake. "I've not had my last question answered. What does your lady-the one you see now-think of what you do?"

"She thinks rather highly of it, if I do say so."

"It gives her pleasure?"

"So I understand from her."

"Does she not think it unusual?"

"I will say that though at first it was rather outside her experience, it was not beyond her amiable tolerance." I was pleased with myself for a few moments, but my smile faded.

"What is it?"

"I was just thinking of how much I'll miss her. Hated to leave her last night. That's why I was so late getting back. Won't happen again, though, Jericho took me to task on the subject of banging doors at dawn and waking the household."

"Father wasn't amused."

I wilted a bit. "I'll apologize to him. Where is he? Not called away?"

"On our last night home? Hardly. He's playing cards with the others."

Father was not an enthusiastic player and only did so to placate his wife. "Is Mother being troublesome again?"

"Enough so that everyone's walking on tiptoes. You know what she thinks of our journeying together-at least when she's having one of her spells. Vile woman. How could she ever come up with such a foul idea?"

I had a thought or two on that, but was not willing to share it with anyone. "She's sick. Sick in mind and in soul."

"I shall not be sorry to leave her behind."

"Elizabeth..."

"Not to worry; I'll behave myself," she promised.

Both of us had come to heartily dislike our mother, though Elizabeth was more vocal in her complaints than I. My chosen place was usually to listen and nod, but now and then I'd remind her to take more care. Mother would not be pleased if she chanced to overhear such bald honesty.

"I hope it helps you to know that I feel the same," I said, wanting to soften my reproach.

"Helps? If I thought myself alone in this, then I should be as mad as she."

"God forbid." I unhooked my leg from the chair arm and rose. "Will you stay or come?"

"Stay. It might set her off to see us walking in together."

True, sadly true.

I ambled along to the parlor, hearing the quiet talk between the card players long before reaching the room. From the advantage of the center hall, I could hear most of what was going on throughout the whole house. Mrs. Nooth and her people were still busy in the distant kitchen, and other servants, including Jericho and his father, Archimedes, were moving about upstairs readying the bedrooms for the night.

Long ignored as part of life's normal background, the sounds tugged at me like ropes. I'd felt it a dozen times over since the plans to leave for England had been finalized. Though not all that happened here was pleasant, it was home, my home, and who of us can depart easily from such familiarity?

And comfort. I hadn't much enjoyed my previous voyages to and fro. The conditions of shipboard life could be appalling-yet another reason for my second thoughts over having Elizabeth along. But I'd seen other women make the crossing with no outstanding hardship. Some of them even enjoyed it, while not a few of the hardiest men were stricken helpless as babes with seasickness.

Well, we'd muddle through somehow, God willing.

I shed those worries for others upon opening the parlor door. Within, a burst of candlelight gilded the furnishings and their occupants. Clustered at the card table were Father,

Mother, Dr. Beldon, and his sister, Mrs. Hardinbrook. Beldon and Father looked up and nodded to me, then resumed attention on their play. Mrs. Hardinbrook's back was to the door, so she noticed nothing. Mother sat opposite her and could see, but was either unaware I'd come in, or ignoring me.

The game continued without break, each mindful of his cards and nothing else as I hesitated in the doorway. For an uneasy moment I felt like an invisible wraith whose presence, if sensed, is attributed to the wind or the natural creaks of an aging house. Well, I could certainly make myself invisible if I chose. That would stir things a bit... but it wouldn't be a very nice thing to do, however tempting.

Mother shifted slightly, eyebrows high as she studied her hand. Her eyes flicked here and there upon the table, upon the others, upon everything except her only son.

Ignoring me. Most definitely ignoring me. One can always tell.

Home, I thought grimly and stepped into the parlor.

Upon entering, I was able to see that my young cousin, Ann Fonteyn, was also present. She'd taken a chair close to a small table and was poring over a book with fond intensity. More Shakespeare, it appeared. She'd developed a great liking for his work since the time I'd tempted her into reading some soon after her arrival to our house. She was the daughter of Grandfather Fonteyn's youngest son and had sought shelter with us, safely away from the conflicts in Philadelphia. Though somewhat stunted in the way of education, she was very beautiful and possessed a sweet and innocent soul. I liked her quite a lot.

I drifted up to bid her a good evening, quietly, out of deference for the others. "What is it tonight? A play or the sonnets?"

"Another play." She lifted the book slightly. "Pericles, Prince of Tyre, but it's not what I expected."

"How so?" I took a seat at the table across from her.

"I thought he was supposed to kill a Gorgon named Medusa, but nothing of the sort has thus far occurred in this drama."

"That's the legend of Perseus, not Pericles," I gently explained.

"Oh."

"It's easy enough to mix them up."

"You must think me to be very stupid and tiresome."

"I think nothing of the sort."

"But I'm always getting things wrong," she stated mournfully.

That was my mother's work. Her sharp tongue had had its inevitable effect on my good-hearted cousin. Ann had become subject to much unfair and undeserved criticism over the months. Mother had the idiotic idea that by this means Ann could be made to "improve herself," though what those improvements might be were anybody's guess. Elizabeth and I had long ago learned to ignore the jibes aimed at us; Ann had no such defenses, and instead grew shy and hesitant about herself. In turn, this inspired even more criticism.

"Not at all. I think you're very charming and bright. In all my time in England I never once met a girl who was the least interested in

reading, period, much less in reading Shakespeare."

"Really?"

"Really." This was true. Nora Jones had been a woman, not a girl, after all. And some of the other young females I'd encountered there had had interests in areas not readily considered by most to be very intellectual. Such pursuits were certainly enjoyable for their own sake; I should be the last person to object to them, having willingly partaken of their pleasures, but they were not the sort of activities my good cousin was quite prepared to indulge in yet.

"What are they like? The English girls?"

"Oh, a dull lot overall," I said, gallantly lying for her sake.

"Did you get to meet any actresses?" she whispered, throwing a wary glance in Mother's direction. Whereas a discussion of a play, or even its reading aloud in the parlor was considered edifying, any mention of stage acting and of actresses in particular was not.

"Hadn't much time for the theater." Another lie, or something close to it. Damnation, why was I... but I knew the answer to that; Mother would not have approved. Though I'd applied myself well enough to my studies, Cousin Oliver and I had taken care to keep ourselves entertained with numerous nonacademic diversions. Then there was all the time I'd spent with Nora....

"I should like to go to a play sometime," said Ann. "I've heard that they have a company in New York now. Hard to believe, is it not? I mean, after the horrid fire destroying nearly everything last year."

"Very. Perhaps one day it will be possible for you to attend a performance, though it might not be by your favorite playwright, y'know."

"Then I must somehow find others to read so as to be well prepared, but I've been all through Uncle Samuel's library and have found only works by Shakespeare."

"I'll be sure to send you others as soon as I get to England," I promised.

Her face flowered into a smile. "Oh, but that is most kind of you, Cousin."

"It will be a pleasure. However, I know that there are other plays in Father's library."

"But they were in French and Greek and I don't know those languages."

"You shall have to learn them, then. Mr. Rapelji would be most happy to take you on as a student."

Instead of a protest as I'd half expected, Ann leaned forward, all shining eyes and bright intent. "I should like that very much, but how would I go about arranging things?"

"Just ask your Uncle Samuel," I said, canting my head once in Father's direction. "He'll sort it out for you."

She made a little squeak to indicate her barely suppressed enthusiasm, but unfortunately that drew Mother's irate attention toward us.

"Jonathan Fonteyn, what is all this row?" she demanded, simultaneously shifting the blame of her vexation to me while elevating it to the level of a small riot. That she'd used my middle name, which I loathed, was an additional annoyance, but I was yet in a good humor and able to overlook it.

"My apologies, Madam. I did not mean to disturb you." The words came out smoothly, as I'd had much practice in the art of placation.

"What are you two talking about?"

"The book I'm reading, Aunt Marie," said Ann, visibly anxious to keep the peace.

"Novels," Mother sneered. "I'm entirely opposed to such things. They're corruption incarnate. You ought not to waste your time on them."

"But this is a play by Shakespeare," Ann went on, perhaps hoping that an invocation of an immortal name would turn aside potential wrath.

"I thought you had some needlework to keep you busy."

"But the play is most excellent, all about Perseus-I mean Pericles, and how he solved a riddle, but had to run away because the king that posed the riddle was afraid that his secret might be revealed."

"And what secret would that be?"

Ann's mouth had opened, but no sound issued forth, and just as well.

"The language is rather convoluted," I said, stepping in before things got awkward. "We're still trying to work out the meaning."

"It's your time to waste, I suppose," Mother sniffed. To everyone's relief, she turned back to her cards.

Ann shut her mouth and gave me a grateful look. She'd belatedly realized that a revelation of the ancient king's incest with his daughter was not exactly a fit topic for parlor conversation. Shakespeare spoke much of noble virtues, but, being a wily fellow, knew that base vices were of far greater interest to his varied audience, sweet Cousin Ann being no exception to that rule.

I smiled back and only then realized that Mother's dismissive comment had inspired a white hot resentment in me. My face seemed to go brittle under the skin, and all I wanted was to get out of there before anything shattered. Excusing myself to Ann, I took my leave, hoping it did not appear too hasty.

Sanctuary awaited in the library. It was without light, but I had no need for a candle. The curtains were wide open, after all. I eased the door shut against the rest of the house and, free of observation, gave silent vent to my agitation. How dare she deride our little pleasures when her own were so empty? I suppose she'd prefer it if all the world spent its day in idle gossip and whiled away the night playing cards, It would bloody well serve her right if that happened....

It was childish, perhaps, to mouth curses, grimace, make fists, and shake them at the indifferent walls, but I felt all the better for it. I could not, at that moment, tell myself that she was a sick and generally ignorant soul, for the anger in me was too strong to respond to reason. Perhaps it was my Fonteyn blood making itself felt, but happily the Barrett side had had enough control to remove me from the source of my pique. To directly express it to Mother would have been most unwise (and a waste of effort), but here I was free to safely indulge my temper.

God, but I would also be glad to leave her behind. Even Mrs. Hardinbrook, a dull, toad-eating gossip if ever one was born, was better company than Mother, if only for being infinitely more polite.

My fit had almost subsided when the door was opened and Father looked in.

"Jonathan?" He peered around doubtfully in what to him was a dark chamber.

"Here, sir," I responded, forcefully composing myself and stepping forward so he might see.

"Whatever are you doing here in the... oh. Never mind, then." He came in, memory and habit guiding him across the floor toward the long windows where some light seeped through. "There, that's better."

"I'll go fetch a candle."

"No, don't trouble yourself, this is fine. I can more or less see you now. There's enough moon for it."

"Is the card game ended?"

"It has for me. I wanted to speak to you."

"I am sorry about the banging door, sir," I said, anticipating him.

"What?"

"The cellar door this morning when I came home. Jericho gave me to understand how unsettling it was to the household. I do apologize."

"Accepted, laddie. It did rouse us all a bit, but once we'd worked out that it was you, things were all right. Come tomorrow it'll be quiet enough 'round here." Not as quiet as one might wish, I thought, grinding my teeth.

Father unlocked and opened the window to bring in the night air. We'd all gotten into the habit of locking them before quitting a room. The greater conflict outside of our little part of the world had had its effect upon us. Times had changed... for the worse.

"1 saw how upset you were when you left," he said, looking directly at me.

Putting my hands in my pockets, I leaned against the wall next to the window frame. "I should not have let myself be overcome by such a trifle."

"Fleabites, laddie. Get enough of them and the best of us can lose control, so you did well by yourself to leave when you did."

"Has something else happened?" I was worried for Ann.

"No. Your mother's quiet enough. She behaves herself more or less when Beldon or Mrs. Hardinbrook are with her."

And around Father. Sometimes. Months back I'd taken it upon myself to influence Mother into a kinder attitude toward him. My admonishment to her to refrain from hurting or harming him in any way had worked

well at first, but her natural inclination for inflicting little (and great) cruelties upon others had gradually eroded the suggestion. Of late I'd been debating whether or not to risk a repetition of my action. I say risk, because Father had no knowledge of what I'd done. It was not something of which I was proud.

"I wish she would show as much restraint with Ann," 1 said. "It's sinful how she berates that girl for nothing. Our little cousin really should come with us to England."

P N Elrod - Barrett 3 - Death Masque

P N Elrod - Barrett 3 - Death Masque